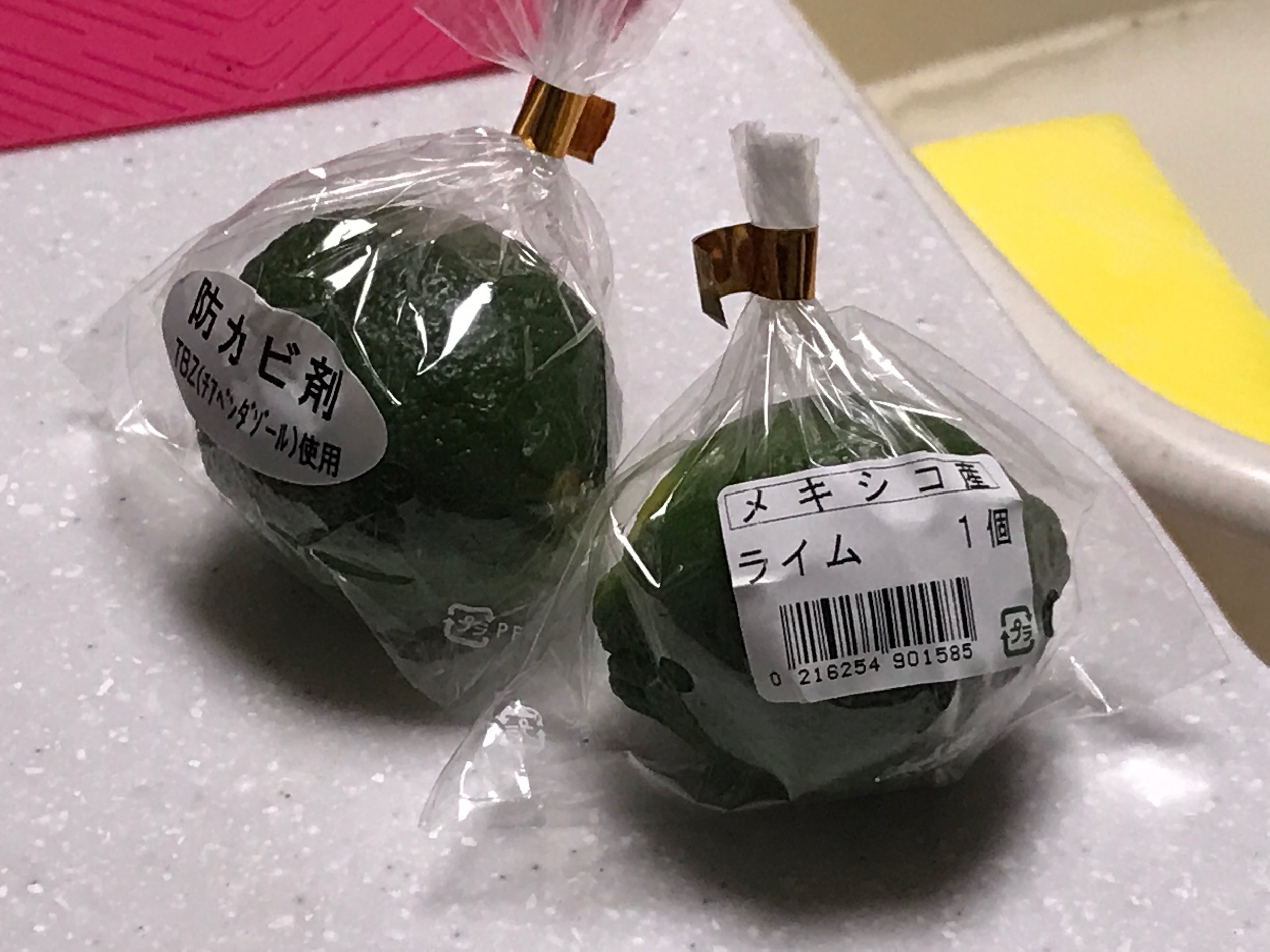

"So, what shall we have for dinner tonight?"

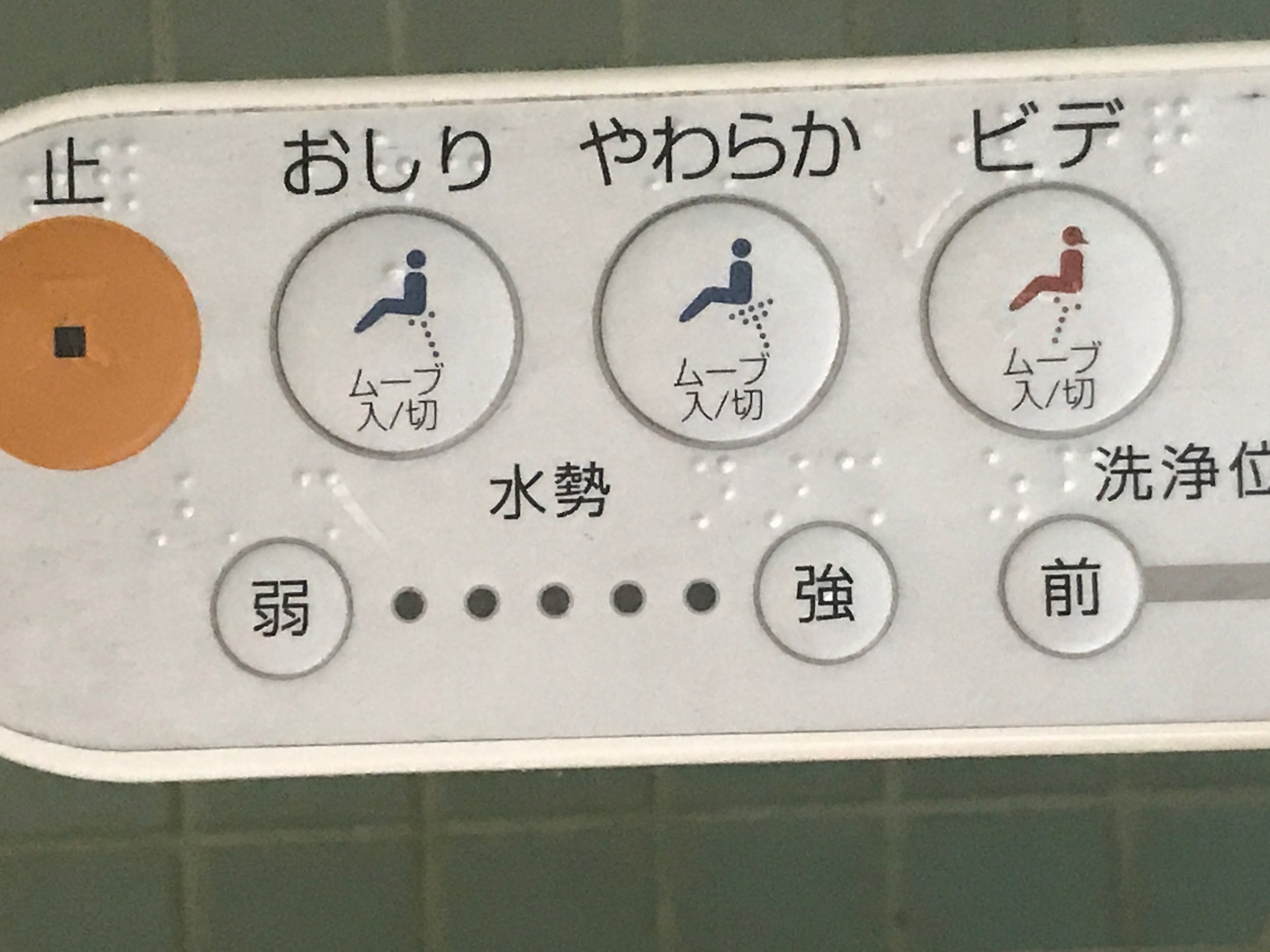

Living in Japan, even just for two weeks, gives me a tiny taste of what it must be like being a migrant arriving in New Zealand, or Europe, or the US. Because I don’t speak the language, I can’t perform the simplest task. Answering the door. Buying a child car seat. Asking directions. Goodness knows what I would do if I had to open a bank account, seek medical help or enrol my children in school. Get a job. What if it had been me having to find out how, where and when to register Zen’s birth.

In Cuba it wasn’t so bad. With a mixture or French, English and a bit of Spanish, I could muddle through; get my message across, get where I needed to go, buy what I needed to buy. And quite a few people spoke English.

Not so here. And Japanese is such a hard language for an English speaker - totally different from anything I know. I can’t imagine ever being anywhere near fluent, even if I studied diligently for the rest of my life. And that means I’d never be able to communicate easily with a Japanese speaker. Never master the bureaucracy of everyday life. Never make a close Japanese friend.

I can see why children of migrants, even very young children, become the ears and mouths of migrant families. And why older people feel isolated and gravitate towards people from their own community - for help, and someone to talk to. I have Saho and Ben here to translate and perform the tasks that need doing. But I hate to think how hard it would be if I didn’t.

I have such admiration for refugees, forced into this situation, through no fault of their own. Stuck in a country they don’t necessarily want to be in, and compelled to operate in a language they don’t speak (and may never read or write) and a culture they don’t understand. Sod that for a game of soldiers, as they say.

A quick cup of tea...